BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE SCIENCE BEHIND THE PROJECT

Here we provide detailed background information on the cellular, clinical, and social factors that we are studying to capture a wholistic look into the health of women living with HIV

Cellular Factors

Key points:

- There are two markers of aging in the cells in the body that we can test to determine someone’s “cellular age”.

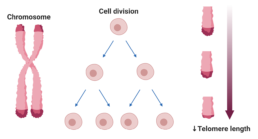

- Telomere length – Telomeres are protective caps at the end of DNA that shorten with age. Telomere length can tell us about someone’s cellular age. Shorter telomere length = older age.

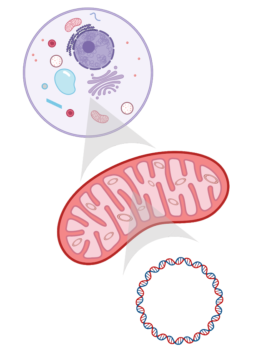

- Mitochondrial DNA – Mitochondria are the energy producing part of cells, and they have their own DNA called “mitochondrial DNA”

- People living with HIV sometimes have shorter telomeres and more mitochondrial DNA damage than their HIV-negative peers, meaning their cells may be aging faster. The reasons for this are unclear, but it may be related to many factors, such as inflammation, stopping and starting cART, comorbidities, hormones, stress, and some social determinants of health. We want to understand this better.

The immune system is a complex system of defense mechanisms in the body that evolved to protect us from disease. Part of this defense system is inflammation, which occurs to help fight against things that may harm the body. Sometimes when the immune system is “turned on” all the time and not able to rest, it can lead to chronic inflammation in the body and oxidative stress (cellular toxicity), both of which can cause damage to DNA and influence early aging of the cells in our body. “Cellular age” is not the same as chronological age. For example, two people may be 50 years old (chronological age), but their cells may function very differently (cellular age). Having healthy cells is a more important predictor of overall health and aging than chronological age.

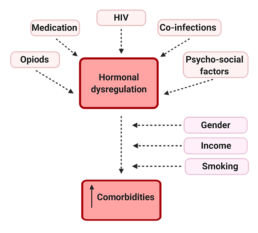

HIV and other viruses such as hepatitis C virus (Hep C) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) that can stay with you for life (they are called chronic or latent viruses) can cause chronic activation of the immune system (the immune system remains ‘turned on’ and is not able to rest). In addition, social stresses such as stigma, violence, and food insecurity also contribute to stress and inflammation in the body. This stress and inflammation could cause hormonal dysregulation in women living with HIV, which may lead to an increase in number of diseases and a decrease in lifespan. Factors such as substance use, HIV medications, amount of HIV virus and CD4 cell count, do not entirely explain differences in markers of aging for women living with HIV. One of these markers is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (energy producing part of all the cells in our body) and the other is the telomere length (the length of DNA at the end of chromosomes). The use of different kinds of HIV medications, as well as being on and off them over time may also have an impact.

Mitochondrial DNA as a marker of cellular aging and DNA damage:

Mitochondria are little organs in cells involved in energy production, calcium balance in the body, cell signalling, regulation of cell death, and hormone creation. They contain their own DNA (mtDNA), which is maternally inherited and codes for important proteins involved in creating energy for cells. mtDNA is particularly susceptible to mutations, which are changes to the genetic code. When many mtDNA mutations accumulate, they can lead to human aging and age-related diseases. mtDNA mutations are central to biological aging, but challenging to detect and quantify.

In people living with HIV, there is evidence that HIV itself affects mitochondria and energy metabolism. In addition, many HIV medications are known to affect mitochondria directly or indirectly, and contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction. For example, a type of ARVs called nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) can block mtDNA replication and lead to mutations and dysfunction. So, cART could affect cellular aging and comorbidities through alteration of mtDNA and mitochondrial function.

Telomere length as a marker of cellular aging:

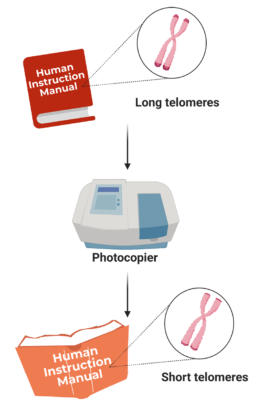

Telomeres are caps that protect the ends of chromosomes (compact DNA) to keep the genetic information protected. Telomere length naturally shortens as we age, due to the cells dividing. You can think of telomeres as the little plastic caps at the ends of shoelaces. If they become damaged, the shoelaces will fray. Similarly, cells become less healthy when telomeres become too short, as the DNA (shoelaces) can become damaged. Telomere shortening can also occur as a consequence of inflammation and DNA damage, but there are many things we can do to prevent this, which we want to study! What are some things you do to live a healthy lifestyle?

Another way to think of telomeres and DNA is in relation to books: DNA is like a manual for how the body functions and telomeres are the hardcovers of the manual. Each time the manual is photocopied, the cover gets more damaged. Overtime, if the cover is too tattered, the whole manual can start to fall apart (Figure 11)! So, once telomeres reach a critically short length, the cell dies or causes inflammation, cellular stress, and DNA damage to other cells. Thus, telomere length is a marker of cellular aging and damage, and predicts mortality (death) among older individuals. It is also established that short telomere length is a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease in the general population.

shorter telomere length = greater cellular age

However, it is unclear what is taking place at the cellular level when telomeres get shorter. In regards to HIV, research has shown that PLWH have shorter telomere lengths than their HIV-negative peers; thus, PLWH may experience increased cellular aging. HIV infection clearly regulates telomere length somehow, likely through immune activation and inflammation. The telomere length in untreated PLWH is shorter, so taking cART may be associated with longer telomere length. However, few studies have investigated telomere length in the immune cells of PLWH treated with cART. This is something that BCC3 is studying.

Thus, chronic/latent viruses may contribute to accelerated cellular aging and the risk of comorbidities among PLWH. It remains unknown whether mitochondrial aging within immune cells may be exacerbated by chronic/latent viral infections and how if this may affect comorbidity risk.

Clinical Factors

Key points:

- Women living with HIV are more likely to have more medical diagnoses (comorbidities) related to age than their HIV-negative peers, and the reasons for this are unclear.

- Reproductive hormones are important for women’s health. When levels of these hormones are not regular (hormone dysregulation), it could potentially lead to an increased risk for poor health.

- It is unknown if women living with HIV experience more hormone dysregulation than other women, but some evidence suggests that they might. There is very little research done on this, so we are leading the way to learn more about the health of women living with HIV!

Clinical factors associated with healthy aging of women include comorbidities, hormones, and reproductive and sexual health. Compared to the general population, WLWH are at higher risk of having comorbidities such as kidney, liver, bone, brain, and heart diseases, depression, anxiety, and some virus-related cancers (such as HPV-related cancers), even among young individuals. The reasons for this are unclear and we want to know if hormone levels are playing a role.

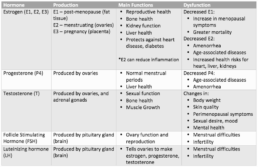

The three major estrogens in women are estrone, estradiol, and estriol:

- Estrone is the main estrogen present in menopausal women

- Estradiol is the main circulating estrogen in women before menopause

- Estriol is present during pregnancy

Other hormones include progesterone and testosterone (see Table 1 for a list of the hormones and their functions). Estrogens and progesterone are responsible for the development and maintenance of reproductive tissues including breasts, ovaries, the uterus and the vagina. Abnormal estradiol and progesterone levels are linked to abnormal uterine bleeding and irregular menstrual periods. Beyond their role in reproductive health, sex hormones are important in the health of multiple organ systems. With menopause, low estradiol levels results in increased risks of health issues related to the heart, liver, and kidneys. Estradiol also helps to fight inflammation.

For women in general, both menopause (starting >1y after final flow) and amenorrhea (no menstrual periods for >3, 6, or 12 months, depending on the study) are associated with decreased levels of estradiol and progesterone. Abnormally low estradiol and progesterone levels are also associated with an increase of many age-associated diseases. Compared with HIV-negative women, WLWH are much more likely to have a history of absent menstrual periods. Given the known protective role of hormones in health, this low hormone state may result in earlier and increased risk for comorbidities.

Another factor influencing hormone dysregulation is opioid use, which can result in a reduction of female sex hormones, including follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estrogens, and progesterone. These changes can result in a state of hormone deficiency, which can lead to abnormal periods and reduced fertility; however, women can recover from this state.

Other factors such as very low body fat, severe physical or psychosocial stress, nutritional deficiency, and chronic illness can also affect women’s hormone levels.

Hormones and biological aging: Mitochondria produce energy, regulate metabolism, and are involved in hormone synthesis. Estradiol improves overall mitochondrial function in tissues such as heart, muscle and brain.

Hormones with HIV and ART: Levels of hormones are influenced by many factors. Among these factors, HIV and ART can both influence hormone use/breakdown and lead to hormone dysregulation. Alongside a high risk of comorbidities, CHIWOS and CARMA data indicate high rates of adverse reproductive health outcomes among WLWH, including a frequent history of missing periods, abnormal menstrual bleeding, and earlier menopause compared to the general population. Whether and how HIV is associated with hormone dysregulation remains unclear, especially given the likely intersection with stress-inducing social determinants of health such as trauma, violence, poverty, substance use, mental health/resilience and gender inequity.

Hormone dysregulation can affect a woman’s life through several avenues. For instance, altered estradiol, progesterone and/or testosterone levels can affect body weight, skin quality, perimenopausal symptoms, as well as sexual desire, mood and mental health (Table 1). Many of these effects may be amplified by HIV associated inflammation. In addition, little is known on how hormonal therapy, hormonal changes and comorbidities may intersect with socio-structural factors to influence the healthy aging of WLWH (Figure 13).

Social Factors

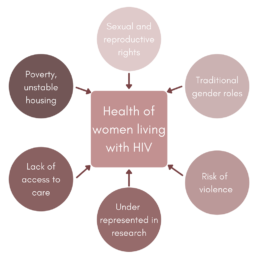

Social factors include the social determinants of health, which are the conditions we are born, grow up, live, and work in, such as: age, income, education, food security, housing security, employment, social support, incarceration, experience with violence, etc. These determinants affect the health and wellbeing of individuals through their ability to access services, healthcare, etc. For WLWH, specific social determinants of health include sexual and reproductive rights, traditional gender roles, poverty and unstable housing, risk of violence, lack of access to care, and an underrepresentation in health research. CHIWOS showed that non-HIV determinants of health are over-represented among WLWH in Canada and play an important role in their health. In order to evaluate the role of HIV in health, it is crucial to also study women not living with HIV with similar social determinants of health. The proposed BCC3 study will be uniquely positioned to do so given that controls will share many risk factors for comorbidities with WLWH.

Health care provider practice and knowledge: Access to appropriate and holistic care is an important determinant of health. WLWH most often receive health care from infectious disease specialists or family physicians. Neither group of health care providers has specific expertise in identifying menstrual cycle disturbances that may indicate hormonal dysregulation. From community members involved in this study, and CHIWOS data, WLWH report that health care providers seldom even ask them about menstrual cycles. Research from CHIWOS reveals that HIV care providers rarely discuss reproductive health issues with their patients. Obtaining this history is essential for providing best care in the health of WLWH.

Samples

What We Hope to Learn from the BCC3 Study Samples:

The BCC3 study uses a wholistic, cell-to-society and women centered approach to gain insight into the factors that impact the health and aging of women living with HIV. Both of our questionnaires and each of the samples that we take give us important insight into the overall health of women. See below to learn more about what each sample can teach us.

- 44 ml (3 tablespoons) of blood will be collected. For participants living with HIV, HIV-related health information will be extracted from your clinical record, if available.

Your biospecimens (samples), collected as part of this study, will be tested for the following:- genetic markers

- sexual and stress hormones

- some common chemistry and hematology tests, like sodium, potassium and hemoglobin

- lab tests like glucose and cholesterol that are used to diagnose diseases of aging such as diabetes and heart, liver or kidney disease

- we will look at the health of cells that fight infection and help heal injuries

- inflammation biomarkers (elements in the blood that show inflammation is present)

- the type of viral infections that are very common in humans can be in the body for a long time

- tests to understand the health of your immune cells

- tests to understand the health and functioning of your mitochondria (energy producing part of body cells)

- tests to understand the health and functioning of your telomeres (the length of DNA at the end of your chromosomes that protects them and shortens with cellular aging)

- your blood may be tested for the Hepatitis B and C viruses as well as HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- If you have menstrual periods and are not using a hormonal contraceptive, included in the above amount of bloodwork will be testing for hormones that require your blood draw to be timed to your menstrual cycle at two different times. Participants will be reimbursed and additional $25 for this extra visit.

A urine sample will be collected to test creatinine and albumin levels. This tells us more about kidney health. For premenopausal women, a second urine will be taken to test for pregnancy.

Two mouth swabs will be collected, these will be used to test for cellular markers of aging in the cheek cells collected. The mouth swabs will also tell us some of what we would learn from blood to help us collect data in a less invasive way.

- We are requesting a hair sample to test for cortisol levels. Cortisol is a stress hormone that has many functions including keeping inflammation down, regulating your blood pressure, helping you manage stress and controlling your sleep/wake cycle. A hair sample will be able to give us information about your cortisol levels over the last 3 months.

- The sample that we collect can be taken from anywhere on the head and is usually taken from a discrete location at the back of the head of the participant’s choosing. The strand of hair collected is cut close to the scalp in order to collect the most accurate and current data possible.

We are requesting two rectal swabs at this visit – to be self-collected by you. Your biospecimens will have testing done in the biological science area called “omics”. This is a field of study that looks at the group classification and measurement of pools of biological molecules that translate into the structure, function, and dynamics of an organism or organisms. This testing will be used to investigate links between the rectal microbiome (as a surrogate for a stool/gut sample) and the other health and aging markers we are looking at in this study.